The Night Road

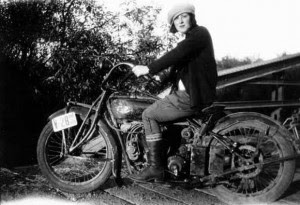

alec vanderboom

Riding north on the Thruway late last night. The entire rest of the world save myself and the steady breathing of the engine--well, maybe every once in a while the cold fingers of the air pressing on my neck, and maybe a sudden awareness of my hands on the grips, the right one starting to cramp--was merely a suggestion. The world reduced to Might exist; might not. And That's not my concern anyway.

Riding north on the Thruway late last night. The entire rest of the world save myself and the steady breathing of the engine--well, maybe every once in a while the cold fingers of the air pressing on my neck, and maybe a sudden awareness of my hands on the grips, the right one starting to cramp--was merely a suggestion. The world reduced to Might exist; might not. And That's not my concern anyway.

There was only me in a large blackness. This led to a long riff on the nature of riding as ideal metaphor: We are all essentially alone; we glance off substances, and we occasionally sense others as well as the ether around us, but we're always riding alone.

Actually, this thought did not occur to me, true though puerile. That's because I was busy doing it. There was no time to think about it.

Here's what I was really thinking: Thank god you got off Long Island intact--those freaking urban drivers are maniacs. I love feeling the risk of an Infiniti taking off my footpeg at 85, don't you? And man, my taillight must look so small they won't know what exactly it is until they hit it. I wonder how well the reflective tape on my jacket and helmet is doing? And does 287 really turn into 87, or do I have to exit? Wait--that was a deer crossing sign: Pay attention! Do not forget!

Does my high beam suck too much power? Is it okay to run it against oncoming traffic?

I can't see the watch I velcroed onto the dash; you know, I thought it had a luminous dial. Oh well. The tach's gone, too, broken; the only thing I have to gauge my passage the speedo, and the wheels and dials (so lightly calibrated! so meticulous in all they measure!) inside of me. That's how we really know we're going, no need for anything else really. I have the sensation of being here. It's small enough and big enough all at once.

Actually, the metaphor is apt. I am going through it alone. My dear friend, the one who has always been there for me, in times of trouble and of happiness but mainly the former, which is why he is so dear, is once again counseling me. "Until you see that being alone is not lonely, Melissa, until you are able to embrace solitude and being with yourself, you will not be happy."

The ride alone last night was composed of solitude, and I could see exactly what Tony meant. I felt it. I've had rides that were lonely, so that's how I knew. This felt different. Full and rich: simple, just a straight shot up the highway on a late summer evening, but sufficient unto itself. I was attentive to the risks, but not their prisoner; I knew I would be home in two hours, but I was happy I was not there yet; I trusted the thousands parts of the little Guzzi valiant underneath me, every working piece (every clap of the tappets audible in their millions when I listened--the amazement of it!) put together with love, in love, and loved in return, which is how she runs.

There have been moments recently, I regret to report, that have caused a lump of self-pity in my throat: Why do I have to handle all this alone? Just a little help. That's all I want!

I know the response this will call forth from my friends, but they can save their energy: I've already excoriated myself for it. Now I would like to report some new knowledge. I can turn anything around, at least in my mind, even if it doesn't stack the firewood or fight with the school district or repair the broken shower. That's because those aren't the real problems, I now see; feeling that they are is the problem. All our big battles are always fought alone, whether our armies contain one, or two. The victories, too, belong to each in isolation. So I can keep the phillips-head screwdriver in the bathroom, and that takes care of that. The rest is just like that ride on the night road: done, and everything.